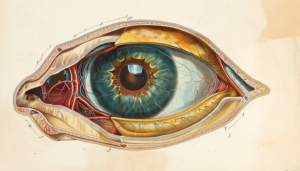

A retinal detachment occurs when the retina, a thin layer of light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye, separates from its normal position. This separation disrupts the retina’s ability to send visual signals to the brain, leading to vision loss that can become permanent if not treated promptly. The condition requires immediate medical attention, as timely intervention can significantly improve the chances of preserving vision. Understanding the symptoms, causes, and treatments for retinal detachment is essential for maintaining eye health and seeking care when needed.

What are the symptoms of a retinal detachment?

Retinal detachment can occur at any age but is more common in people over 40. They occur more often in men than women, and in Caucasians more than African Americans. [4] A retinal detachment does not usually cause any pain. Although a retinal detachment can occur without any symptoms at all, it is important to seek immediate medical care of you experience any of the common symptoms of retinal detachment, including:

- Flashes of light in one or both eyes (photopsia) – These are brief, lightening or sparkler-like, and often at the edge of the visual field. More likely to occur with eye movement. Easier to detect when eyes are closed or in a dark place.

- Shadow or curtain appearing over your vision, or coming down over vision

- New and sudden loss of vision, or vision that gets worse over time. Often first noticed in peripheral (side) vision and accompanied by other symptoms

- Sudden appearance of many floaters (specks, cobwebs or strands that appear to float through your vision).

- Heavy feeling in the eye

- Straight lines appear curved

- The sudden appearance of many floaters is a symptom of retina detachment.

What causes retinal detachment?

There are many reasons why someone may experience a retinal detachment, and some occur spontaneously, usually in thinning areas of the retina, appearing to have no known cause. [1] Some known causes of retinal detachment that may put you at increased risk include:

- Eye injury or trauma – retinal detachment may occur at the time of the injury or up to several years later.

- Trauma or blow to the head – retinal detachment may occur at the time of the injury or up to several years later.

- Complication of an eye disease, disorder or surgery – uveitis or cataract surgery

- Myopia (nearsightedness) – particularly high myopia (-6.0D or higher)

- Untreated retinal breaks, holes, lattice or tears

- History of having had a retinal detachment in the other eye

- Having a family member that has had a retinal detachment

How is a retinal detachment diagnosed?

The only way to confirm a diagnosis of retinal detachment is to have a dilated eye examination by an ophthalmologist or optometrist. Dilated means that drops are put in the eyes that will widen your pupils so that the examiner can see through the pupil to the back of the eye, having a clearer view of the retina and any tears, breaks, holes or detachment.

Prior to the examination you will likely have an assessment of your vision (visual acuity), and you will be asked questions about any symptoms you have experienced.

Prior to the dilated eye exam, you will likely have to take a visual acuity test and will be asked questions about any symptoms you’ve experienced.

Dilated pupils may make eyes very sensitive to light and cause vision to be blurred for several hours afterward. It is often recommended to bring someone to drive after having eyes dilated.

Additional imaging or assessments may be performed by your ophthalmologist or optometrist. These may include an ultrasound of the eye, photographs of the retina with or without special dye, or optical coherence tomography (OCT) to show the details of the layers of the retina.

Are there different types of retinal detachment?

Yes, there are three different types of retinal detachment:

Rhegmatogenous – The most frequently occurring type of retinal detachment and its most common cause is aging. [3] Over time, the vitreous begins to shrink and liquify. As it does, it can cause the fibers of the posterior hyaloid face (a membrane that connects the vitreous to the retina) to separate from the retina, known as a posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). A PVD is a normal process and is not usually visually threatening, but in rare cases can cause a retinal detachment. In this type of retinal detachment, a break or tear in the retina allows for fluid to pass through the layers of the retina, collecting beneath and pulling the retina away from the back surface of the eye. The separation of the layers cuts off the blood supply and nourishment to the retina and inhibits its ability to function properly.

Tractional – A build-up of scar tissue on the retina’s surface can contract and causes the retina to separate and fluid can pool between the layers. A tractional detachment is typically seen in people with other conditions, such as poorly controlled diabetes.

Exudative (Secondary)—Frequently caused by retinal diseases, including inflammatory disorders and injury/trauma to the eye. In this type, fluid leaks into and accumulates into the area underneath the retina, but there are no tears or breaks in the retina. This type of retinal detachment is usually caused by injury or other eye conditions such as age-related macular degeneration, inflammatory disorders or tumors.

Retinal detachments may also be classified by whether, at the time of diagnosis, the area of retinal detachment includes the macula or not. The status of the macula is the primary factor of how emergent the eye is. If the macula, specifically the fovea, is still attached, referred to as “mac-on” it is considered an emergency and surgery should be performed within 24 hours. It is urgent, because the macula is critical to maintaining central vision and if still attached, this vision is preserved. In eyes where the macula has detached, “mac-off”, prognosis for central vision recovery is poorer. In these cases, surgery is less urgent, but usually performed within 1 week.

Can a retinal detachment be prevented?

Prevention of retinal detachment can be difficult as they typically occur without any warning. For retinal detachments caused by trauma or eye injury, you can take steps to avoid the initial injury by wearing appropriate eye protection during sports or activities that may put your eyes at risk.

You may be unable to prevent most retinal detachments, but having regular eye examinations can detect retinal thinning, or treat small holes, breaks or tears before they become full retinal detachments. Small tears or holes in the retina are usually treated and repaired with a special type of laser (for retina, not to correct refractive error) in the ophthalmologists’ office. The laser makes tiny burns, tacking, or ‘welding’ the retina back into place. Also, seeking treatment for retinal detachment as soon as possible helps to increase the likelihood that permanent vision loss can be prevented.

How is a retinal detachment treated?

A retinal detachment will require treatment with surgery and must be managed by an ophthalmologist, specifically a retina specialist or vitreoretinal surgeon. If a retinal detachment is found by an optometrist or other healthcare provider, you will be immediately referred to an ophthalmologist. Without surgical intervention, there is a very high risk of complete vision loss.

Retinal detachment surgery is usually performed in a hospital or surgical center. It can be done under a general anesthetic, or some surgeons prefer to use lighter anesthesia or sedation.

There are several techniques that may be used to repair a retinal detachment, depending on its severity and location.

A laser (photocoagulation) or freezing probe (cryotherapy, cryopexy) may also be used to ensure the retina stays in the desired position by tacking down and sealing some areas. The laser is directed through a special lens or ophthalmoscope that puts small precise burns on the tissue around the area of the retinal tear. This creates a small scar that tacks or “welds” the tissue back together. Similarly, freezing or cryotherapy involves creation of a small scar using extreme cold to reconnect the retina to the wall of the eye.

Image result for laser for retinal detachment

A scleral buckle can be used for cases of retinal detachment. It involves a small synthetic band (silicone rubber or sponge) that is attached to the outside of the eye (the sclera) and it gently puts pressure on the outside wall of the eye, gently pressing it back against the detached area of the retina.

A vitrectomy is commonly performed, and involves removal of the vitreous, the jelly-like substance in the middle of the eye that helps the eye maintain its shape. During a vitrectomy very fine instruments are inserted into the eye through a small incision in the sclera, the white part of the eye. The vitreous is removed and replaced with gas or silicone oil that presses the detached layers of the retina back into their normal position. The eye will eventually replace the gas with its own natural fluid (aqueous humor) during the healing process. Eyes that receive silicone oil may have to return to their surgeon to have it removed once healing is complete, usually within 2 to 8 months.

There are small risks associated with retinal detachment surgery, including complications related to cataract formation, eye infection, allergic reaction to medications, bleeding (hemorrhage) in the eye, glaucoma or changes in vision.

Tiny instruments are inserted into the eye in a vitrectomy. Using small incision sutureless vitrectomy technique, there is less discomfort after surgery and recovery is faster.

Pneumatic retinopexy (air bubble injection) is a procedure that can be considered in cases of uncomplicated retinal detachment. The surgeon injects a small air bubble into the vitreous cavity inside the eye. The bubble gently pushes the detached area of retina back into place.

In cases where a gas or air bubble is used, the patient may be required to lay face down or hold their head in a specific position to help the air bubble keep pressure on the detached area of retina.

If you get an air or gas bubble in your eye, you will be advised against air travel or any travel through extreme changes in altitude until your surgeon advises you are allowed to do so. A rapid increase in altitude can lead to a dangerous rise in pressure within the eye. With an oil bubble, air travel is safe.

What will my vision be like after retinal detachment?

The good news is that with advancements in technology, instrumentation, and surgical skill, more than 90% of retinal detachments can be successfully treated. [5, 2] The quality of vision or degree of vision loss after retinal detachment repair is difficult to predict.

Some eyes will require more than one surgery, and the final vision outcomes may not become apparent for several months after surgery. Sometimes, it is not possible to reattach the retina, and the person’s vision will continue to deteriorate. For some people, their pre-retinal detachment vision may never return fully, and some patients do not recover any of the lost vision.

Visual outcomes are typically better if the retinal detachment surgery is performed before the area of the retina that includes the macula (center area of the retina responsible for fine, detailed vision) becomes detached.

Importance of Maintaining Overall Eye Health

Retinal detachment is a serious condition that underscores the importance of proactive eye care. While it cannot always be prevented, maintaining overall eye health can help reduce the likelihood of developing age-related eye conditions that may increase risk.

Eye health supplements, like Macutene Protect, offer valuable support for maintaining the integrity and function of your eyes, both before and after procedures like retinal detachment surgery. Packed with nutrients from the AREDS2 formula, these supplements nourish the eyes with essential carotenoids and antioxidants, promoting resilience and overall well-being for aging eyes. As always, consult with your eye care provider about the best strategies to support your eye health and recovery.

References:

[1] Burton TC. The influence of refractive error and lattice degeneration on the incidence of retinal detachment. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1989;87:143-157. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1298542/

[2] Haugstad M, Moosmayer S, Bragad?ttir R. Primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment – surgical methods and anatomical outcome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2017 May;95(3):247-251. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27860442

[3] Liao L, Zhu XH. Advances in the treatment of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019 Apr 18;12(4):660-667. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6469565/

[4] Steel D. Retinal detachment. BMJ Clin Evid. 2014; 2014: 0710. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3940167/

[5] Yorston D, Jalali S. Retinal detachment in developing countries. Eye (Lond). 2002 Jul; 16(4):353-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12101440